In November 2020, reports emerged on social media and in the Pakistani press that al-Qaida chief Ayman al-Zawahiri had recently died of natural causes, possibly in Afghanistan. Born in 1951, the Egyptian jihadi veteran has been at the helm of al-Qaida since Osama bin Ladin’s death in the raid on Abbottabad, Pakistan in May 2011. During this time he has been highly visible as the face of the organization, delivering numerous audio and video addresses and offering written guidance to its members and branches. While there have been periods when he was incommunicado and his fate uncertain, never before have rumors of his demise swirled with such intensity. The release last week of a new video featuring al-Zawahiri has only reinforced those rumors, raising questions about the future of al-Qaida’s leadership and its future as an organization.

The Wound of the Rohingya

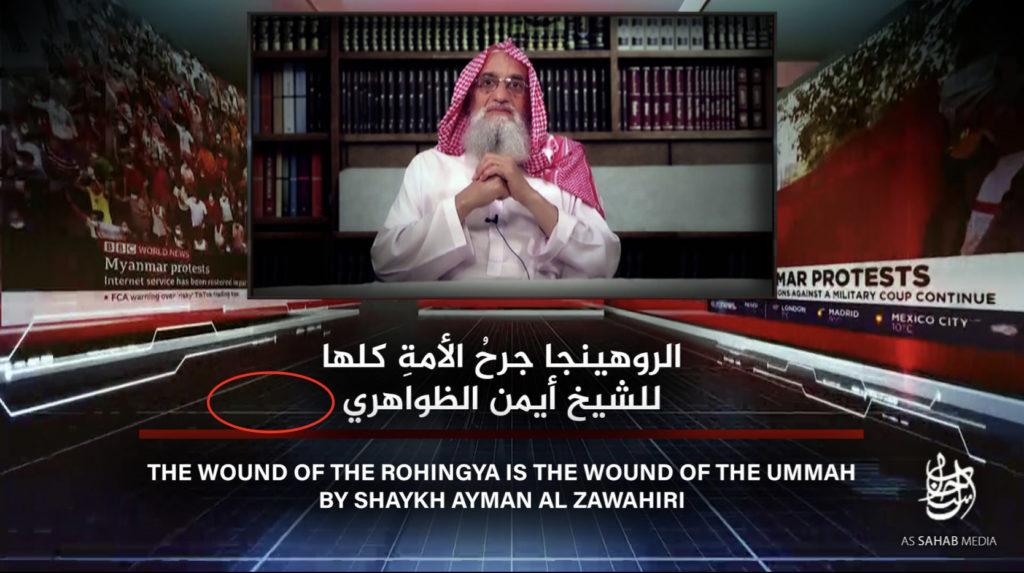

The new video, released on March 12, 2021 and titled “The Rohingya Are the Wound of the Entire Umma,” is peculiar in several respects. First, though it is advertised as a video address by al-Zawahiri, he is not in fact the main speaker. That role is played by an unidentified narrator, who introduces the subject (the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar and the world’s failure to do something about it) and provides the vast majority of the commentary. Al-Zawahiri’s voice can be heard (he does not actually appear in the video) on just six occasions, in snippets ranging from eleven seconds to a minute and a half. In total, he speaks for just three minutes and forty-five seconds in the nearly 22-minute video. While news coverages clippings take up a lot of this time, and that is normal in these sorts of videos, it is not normal for al-Zawahiri to play second fiddle to another speaker.

Al-Zawahiri, it seems, did at some point record an address on the subject of the Rohingya genocide. But the impression given by the video is that this was recorded so long ago that it needed trimming and repackaging in order not to seem dated and timeworn. In one of the six snippets, al-Zawahiri speaks of “the democratic government of Myanmar,” indicating that his recorded words are not recent. The narrator, by contrast, refers to “the military coup in Myanmar,” showing that at least he is up to date on current affairs. Al-Zawahiri’s words are indeed so general that they could have been recorded as long ago as 2017. Nothing in his three minutes and forty-five seconds offers anything remotely approaching proof of life.

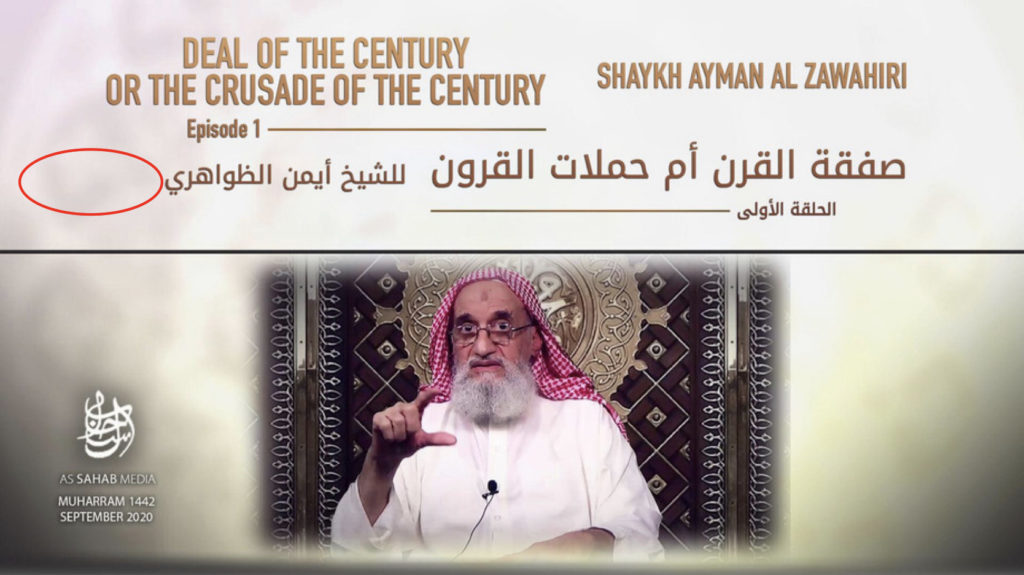

In his last video, al-Zawahiri also did not refer to recent events. Released on September 11, 2020, this was a most unusual video for al-Qaida to put out on the anniversary of 9/11. Billed as the first installment of a series titled “Deal of the Century or Centuries of Campaigns?” its general subject is the Trump administration’s policies regarding Israel. At the beginning of the video, al-Zawahiri describes some of the Trump administration’s recent moves, such as relocating the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, as part of “the long-running struggle between the Muslims and the Crusaders.” Yet the bulk of his address takes the form of an extended refutation of an al-Jazeera documentary from July 2019 that asserted links between al-Qaida and Bahraini intelligence. Al-Zawahiri made no reference to anything more recent than that.

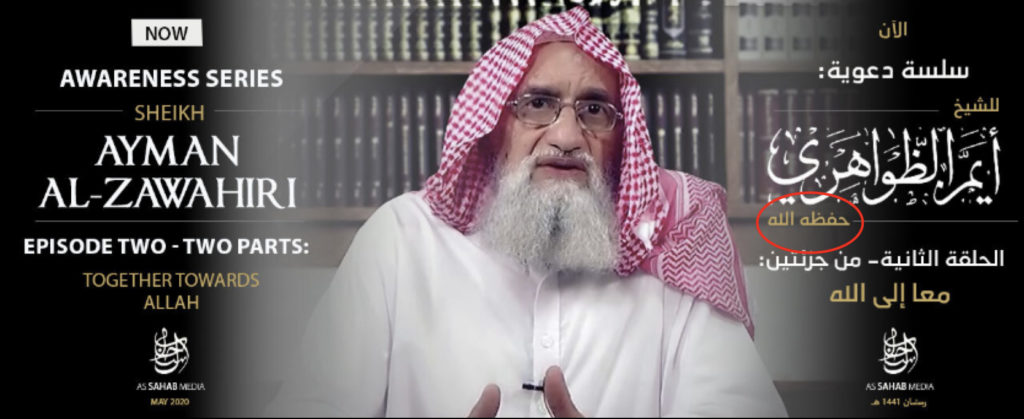

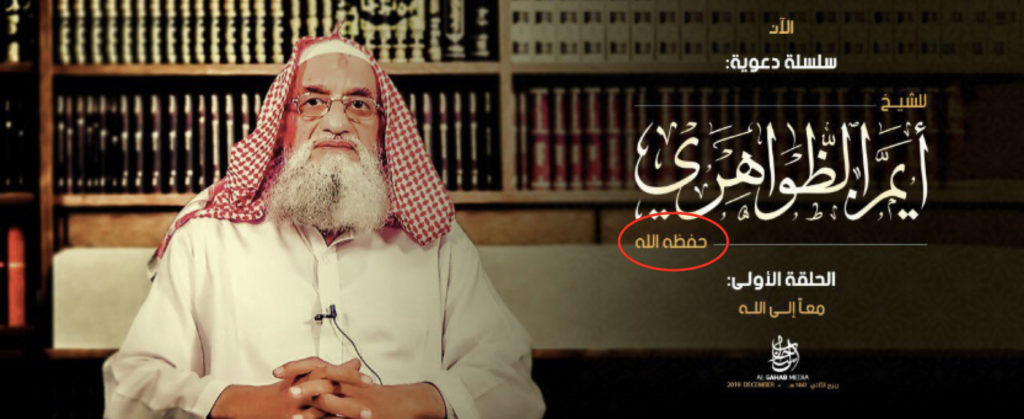

Another peculiarity of the Rohingya video, as pointed out by Wassim Nasr, is the omission of the phrase “may God preserve him” from its usual place after al-Zawahiri’s name, both in the announcement for the video and in the video itself. In jihadi media products, the words “may God preserve him” usually follow the name of a speaker/author who is alive, whereas the words “may God have mercy on him” usually follow the name of a speaker/author who is dead. The absence of either of these expressions here is striking, particularly in the context of rumors of al-Zawahiri’s death. The phraseology was also missing from al-Zawahiri’s “Deal of the Century” video. By contrast, “may God preserve him” followed al-Zawahiri’s name is his video from May 2020, as it did in nearly all of his videos from 2019. While occasionally al-Qaida has neglected to include the phrase in videos of al-Zawahiri in the past, to do so twice in a row under the current circumstances is to give the impression that he very well could be dead.

Jihadi reactions

Following the release of the video, supporters of the Islamic State trolled supporters of al-Qaida on Telegram, sometimes using the hashtag @where_is_al-Zawahiri (#أين_الظواهري). Sawt al-Zarqawi, a prominent commentator, urged those in the Islamic State camp to use the hashtag and to give the “apostate” al-Qaida lovers hell in retaliation for how they responded to the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October 2019. “Flog them and gloat over them,” he wrote, “as those accursed ones did before when they rejoiced and exulted in the martyrdom of Shaykh Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, may God accept him … today the shoe is on the other foot.”

Another prominent supporter of the Islamic State, known as Baha’, called the video a failed attempt “to prove that al-Zawahiri is alive.” While the video was presented as being a new address by al-Zawahiri, he wrote, it obviously was not, and “even the supporters of al-Qaida recognized this time that it is an old production.” More discouraging for them still, he continued, was the absence of the phrase “may God preserve him,” an omission that “invites speculation.” In another post, Baha’ wrote that the video, rather than reassuring al-Qaida supporters about their emir’s status, instead had the effect of “fueling speculation about al-Zawahiri’s fate and the fate of al-Qaida in its entirety.”

Baha’s own take is that al-Zawahiri is long dead and that al-Qaida, for whatever reason, is trying to cover it up: “All of this muddling … confirms that which is already established, which is that al-Zawahiri died a long time ago. Foolish al-Qaida’s current efforts are akin to trying to cover up the sun with a sieve.” But al-Qaida may not be ready, he added, to announce the death of its leader. Alluding to the two-year period from 2014 to 2015 when al-Qaida urged its members to give bay‘a, or allegiance, to Taliban leader Mullah Omar as their supreme authority even though he had been dead since 2013, Baha’ quipped that “giving bay‘a to the dead is a registered al-Qaida trademark.”

The online supporters of al-Qaida, as Baha’ correctly noted, made no effort to convince themselves that al-Zawahiri’s video was new and that it furnished proof of life. To the contrary, some of them began to entertain the possibility that al-Zawahiri had died. In a post released the day after the video, Jallad al-Murji’a, one of the more outspoken pro-al-Qaida commentators on Telegram, praised al-Zawahiri as one of the giants of the jihadi movement while minimizing the significance of his possible death. Jihad is not about any particular leader or organization, he reminded his readers, and all of us, including al-Zawahiri, will one day die. “There will come a day when [al-Zawahiri] dies,” Jallad al-Murji’a wrote, “whether that is today or tomorrow, for death will afflict all of us.” In that event, al-Qaida “may pass through stages of weakness,” but in one form or another it will endure. This is because al-Qaida “is more than just an armed group; rather, it is an idea and methodology and creed that will not expire with the death of its adherents.” None of this, he said, was to affirm or deny the rumors of al-Zawahiri’s death, only to remind everyone that his death will eventually come and that the jihad will continue.

A similar sentiment was expressed by another pro-al-Qaida personality, Warith al-Qassam, who in a post informed al-Qaida’s unbelieving adversaries that the organization does not fight on behalf of any particular individual. “If for the sake of argument we accept your claims that the jihad will end with the death of our shaykh,” he wrote, “then the jihad would have ended more than fifteen years ago with the death of the Imam Abu ‘Abdallah [i.e., Osama bin Ladin].”

These kinds of statements do not constitute acknowledgment of al-Zawahiri’s death, but they do show that al-Qaida supporters are beginning at least to take seriously the idea that their leader has passed.

The Problem of succession

The possibility of al-Zawahiri’s death raises the question of who will succeed him. The process of choosing a successor could be a difficult one.

Several years ago, al-Qaida put in place a succession plan providing for an orderly transition, but it may be of little help today. The plan was detailed in a set of documents leaked by the Syrian-based jihadi al-Zubayr al-Ghazzi in the course of the dispute between Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and the group of al-Qaida loyalists in Syria. The documents, from 2014, are the handwritten statements of six high-ranking members of al-Qaida pledging to honor the succession plan. The line of succession to al-Zawahiri is described as follows: First, Abu al-Khayr al-Masri, then Abu Muhammad al-Masri, then Sayf al-‘Adl, then Nasir al-Wuhayshi, and then another person to be chosen by al-Qaida’s shura council. Out of the four men named here, three are now dead: Nasir al-Wuhayshi was killed in a drone strike in Yemen in 2015, Abu al-Khayr al-Masri was killed by the same means in Syria in 2017, and Abu Muhammad al-Masri was gunned down in Iran (most likely by Israeli agents) in 2020. That leaves Sayf al-‘Adl as the only surviving candidate, but his elevation could be complicated by the fact that he is living in Iran.

The six documents detailing the succession plan clearly state that for a candidate to be given bay‘a as emir he must be present in Khurasan (i.e., the Afghanistan-Pakistan region) or in one of al-Qaida’s branches. That would seem to rule out anyone living in Iran, including al-‘Adl, who is forbidden from leaving the country in accordance with the terms of a 2015 prisoner exchange deal. However, the deal with Iran was reached after these succession documents were written, leaving open the possibility that the restriction on his candidacy no longer applies. While the prisoner exchange deal forbade al-‘Adl from leaving Iran, it also enabled him to live a more normal life and to operate more freely. Thus he may feel perfectly comfortable claiming the mantle of al-Qaida’s global leadership. Even so, it would be problematic for ‘Adl to assume the emirship while still living in Iran, a country routinely described by al-Zawahiri as an enemy state and seen as such by the vast majority of al-Qaida’s supporters. Such a situation would almost certainly alienate al-Qaida’s support base of hardline Jihadi Salafis and possibly some of its commanders. So if al-‘Adl were indeed to succeed al-Zawahiri, he would be wise to do so discreetly—and to try to leave Iran for another safe location as soon as possible.

If al-‘Adl is disqualified, however, on the basis of his location, then perhaps the decision on a successor would fall to al-Qaida’s shura council. In that case the picture becomes more obscure. One possible candidate in this scenario is ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Maghrebi, al-Zawahiri’s Moroccan-born son-in-law who is in charge of al-Qaida’s main media platform, al-Sahab. But he too, according to the U.S. State Department, is based in Iran. Incidentally, al-Maghrebi is the author of one of the six pledges outlining the 2014 succession plan. Two of the other authors of these pledges, Abu Ziyad al-‘Iraqi and Abu Dujana al-Basha, are no longer alive. Perhaps one of the other three authors (Abu Hammam al-Sa‘idi, Salih ibn Sa‘id al-Ghamidi, and Abu ‘Amr al-Masri) is a possible candidate, but there seems to be no publicly available information about who or where they are.

Another complicating factor in the succession process is the Taliban’s ongoing negotations with the Afghan government and its hopes for a complete U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Al-Qaida, as is well known, has long enjoyed a close relationship with the Taliban and even presents itself as ultimately subservient to the Taliban leader. Yet in seeking to get the United States to agree to a military withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban has sought to minimize the relationship with al-Qaida, going so far as to deny that any al-Qaida members are present in Afghanistan. That is of course false (in summer 2020 CENTCOM commander Kenneth McKenzie located al-Zawahiri in eastern Afghanistan, and in fall of last year Afghan special forces eliminated al-Qaida’s media chief in Ghazni Province), but the Taliban’s interest in making it seem that al-Qaida is of little significance could have an effect on succession.

The Taliban appears to have asked the al-Qaida central leadership to keep a low profile while it negotiates a U.S. exit. Hardly any al-Qaida videos have been released since the signing of the Doha accord in February 2020. So if al-Zawahiri were to have died, and especially if he died while living in Afghanistan, the Taliban might request that al-Qaida not announce it—and thus delay announcing a successor. That delay could grow into a long one, as the Biden administration may never agree to a complete withdrawal of U.S. forces.

Three distinct possibilities

While al-Zawahiri’s death is not confirmed, all signs seem to be pointing in that direction. Even al-Qaida itself, by leaving out the words “may God preserve him” from its latest video, seems to be signaling that he could be dead. The first and most likely possibility, then, is that al-Zawahiri has died but that al-Qaida does not yet wish to confirm it, either because it is playing for time as it manages a succession or because the Taliban has asked it not to, or both—or perhaps for some other reason.

Yet if this is the case, the question remains why al-Qaida would put out the Rohingya video in the first place. What possible benefit is there in fueling speculation that al-Zawahiri is dead? Is the purpose to send a message to al-Qaida’s global membership that a transition may be underway? Perhaps that is so, but another explanation is also possible.

The second possibility is that al- Zawahiri is not dead but that al-Qaida wants us to think that he might be. In other words, al-Qaida is deliberately fostering ambiguity for some strategic purpose, perhaps because al-Qaida (in cooperation with the Taliban) wants to broadcast to the United States and the international community that al-Qaida is weak and fragile—and thus not worth sticking around in Afghanistan for. That, however, may be a bit too conspiratorial to countenance. As the saying goes, never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity or incompetence.

That leads to the third possibility, which is that the al-Qaida leaders responsible for the group’s media production simply do not know if al-Zawahiri is dead or not. They have heard the rumors of his death but are just as in the dark as the rest of us. If this were true, it would account for the withholding of “may God preserve him” or “may God have mercy on him” from after al-Zawahiri’s name, but it would not account for the decision to release the video in the first place.

Whatever the case may be, al-Qaida’s supporters cannot be feeling very good about their organization right now. What is going on at the top of al-Qaida is not entirely clear, but it appears to be a symptom of a deeper dysfunction and existential crisis afflicting the group. Several of al-Qaida’s local affiliates are doing quite well today, but as a centralized organization al-Qaida has the look of a group in disarray. Over the past decade it has lost control of its affiliates in Iraq and Syria. It has lost numerous leaders in decapitation strikes or assassinations, and those who have survived appear powerless and constrained. Sayf al-‘Adl, the presumptive successor to al-Zawahiri, lives in a country that al-Qaida claims to be at war with. Other al-Qaida leaders live under the authority of a group, the Taliban, that seems interested in reigning it in (at least temporarily). Meanwhile, al-Qaida’s principal stated objective remains attacking the United States, though it has not succeeded in doing so on a large scale since 9/11. And while it is generally thought of as a Jihadi Salafi group, al-Qaida occasionally makes overtures to the Muslim Brotherhood, as it did in this most recent video. In short, there is a lot of dissonance here. Whether al-Zawahiri is dead or alive, al-Qaida has a lot of problems it needs to sort out. Any successor might find the challenge insurmountable.

3 Responses